It’s taken me quite some time to write up this post because of a prolonged foray into the meaning of ‘soogee’ and the origins of this dish.

In Singapore and Malaysia today, it’s usually spelt ‘sugee’ but I quickly discovered that there are alternative spellings – ‘sugi’, ‘suji’, ‘sooji’, ‘soojee’ – which are used in India. However, suji is the Hindi term used in North India, whereas in South India, it goes by the name ‘rava’, ‘ravva’, ‘rawa’ (wonder if someone can help me – is this in Telugu?). You might like to refer to glossaries of Indian cooking here, here, here and here.

Now this strong Indian connection intrigued me because Sugee Cake is firmly entrenched in Singapore & Malaysian as a distinctly Eurasian dish, as you can see here and here, while Mary Gomes‘ Eurasian Cookbook describes it as the ‘typical Eurasian wedding cake’ and at the restaurant at the Singapore Eurasian Association, Quentin’s, ‘the sugee cake made by his mother is always a hot favourite’. The status of Sugee Cake as a perennial local favourites is reflected by its inclusion in Singapore secondary school home economics textbooks :)!

Although categorised as a single ethnic community, Eurasians in Singapore and Malaysia have a diverse range of origins (Portuguese, Dutch, British – in chronological order of the appearance of colonial powers in Malaya, mixed with different Asian ethnicities, usually Indian or Chinese). However, what is usually presented as Eurasian culture in Singapore is the colourful Portuguese variety, which traces its roots back to the community in Malacca, a town conquered by the Portuguese in 1511. The Portuguese had also landed in Goa, on the west coast of India, in 1510, and established a colony there. Portuguese-Indian Eurasians from Goa soon migrated to Malacca in the following century or so, before the Portuguese lost Malacca to the Dutch in 1641.

It therefore seems most likely that Sugee Cake originated on the Indian subcontinent, an offshoot of Indian sweets made with sugee, such as halwa and kesari (this recipe being the version from a Singaporean with roots in Kerala, a state also on the southwest coast of India not far from Goa). Halwa and kesari, like many Asian sweets, are both cooked on the stove top, whereas Sugee Cake is baked in an oven, like a European cake, which represents the Eurasian element in this recipe.

But what is sugee/soogee/suji/sooji? It’s semolina, which is in fact a product made from durum wheat (what Italian pasta is made from). The Penguin Companion to Food tells us that durum wheat is a very hard variety of wheat and ‘when coarsely milled, the brittle grains fracture into sharp chips, and it is these which constitute ordinary semolina’. Semolina is found in cuisines all round the world, from British semolina pudding, to German rote Grütze, to Russian gurieveskaya kasha, to Greek ravaní (related to South Indian rava?), to Middle Eastern halva (clearly connected to Indian halwa).

Semolina, like other flours, can be milled in different ways and ground into different textures. According to this document about the wheat industry in India, suji is ‘coarse semolina’ and rava is ‘fine semolina’. Most recipes don’t make a distinction between suji, rava and semolina, so perhaps it depends on how fussy you are.

Besides Indian sweets and Sugee Cake, semolina is used in other Singaporean/Malaysian ethnic cuisines, such as the Malay Kueh Bingka Suji (N.B. there are other types of kueh bingka made with tapioca, also a popular nonya dish) as well Sugee Cookies, which are a mainstay of Chinese New Year snacking (see recipe here) as well as popular for Malay Hari Raya (see photos here). Most home bakers would probably pick up the most commonly available semolina flour by local flour mill, Prima Flour, which is found every supermarket.

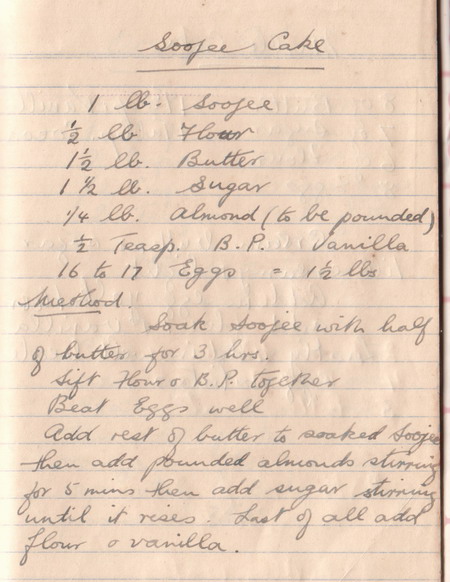

Grandmother’s recipe below doesn’t include baking instructions, so you might want to cross-reference with other Sugee Cake recipes, such as this one from Rose’s Kitchen or this one by Amy Beh, the well-known Malaysian food writer. However, both use the creaming method which doesn’t feature in grandma’s recipe at all, and the length of time one is instructed to soak the semolina varies from 1 1/2 hrs (Amy Beh), to 3 hrs (grandma) to 8 hrs (Rose’s Kitchen). All the recipes use a heart attack-inducing number of eggs though! Reminds me of grandma’s Marmer/Marble Cake recipe :).

Read Full Post »