“Chye-yean” (菜燕),Chinese (Hokkien?) for agar-agar. However, I have only ever heard the term ‘agar-agar’. The first thing that pops into my mind are the colourful agar agar jellies from my primary school tuckshop. Baking Mum has some exquisite versions of the traditional layered agar agar dessert here and here.

Most interesting to me is the strong historical Malayan connection to this seaweed-derived product, which is evidenced by the fact that its international name today is the Malay word ‘agar’. The entry on SinglishDictionary.com lists fascinating colonial references to agar in Malaya from 1813, 1820 and 1894 and opens a little window on how this Southeast Asian item made its way further afield.

While some equate agar agar with Japanese kanten, this information says that in Japan, kanten and agar-agar refer to separate products made from different kinds of seaweed and have different textures. The additional details here suggest that outside of Japan, this distinction may not be so important and the term ‘agar-agar’ is used in a broad fashion to denote a whole family of seaweed products.

Agar has the advantage of not melting, which is very handy in our tropical weather. It can even set without refrigeration.

Another wonderful thing about agar agar is that you can use it to gelatinise (is there such a word?) almost any liquid, except vinegar and foods high in oxalic acid, which includes spinach, chocolate and rhubarb (read more in this article).

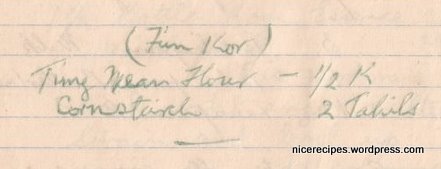

Agar agar comes in two forms — long strips and powder. I assume that back in grandmother’s time, they didn’t have agar agar processed into easily-spoonable powder and packaged in handy single-use sachets that we use today :), so this most likely refers to the strips.

To use agar strips, rinse in cold water first and leave them to soak until softened. Then boil in the required amount of liquid until it melts.

I have no idea why there are two sets of quantities for the Chye Yean with one being twice as diluted as the other. The amount of liquid used affects the hardness of the agar jelly when it sets, so make it less dilute if you like a ‘crunchy’ texture.

Tahils and katis (“K.” in the recipe notes )are such nostalgic measures of weight :), bringing to mind vivid memories of following grandmother to the wet market as a young child. See this conversion table for katis (cattys) and tahils to metric or imperial measurements.